Mass Immigration or Technological Progress: Pick One

How cheap labor and free trade spell the end of humanity's future

A common argument for mass immigration from India is that America “needs” immigrants in order to remain competitive in science and tech, an argument that has unfortunately been advanced by the Trump administration in the past couple of weeks. These arguments are always made by way of anecdote, e.g. “BUT ELON MUSK WAS AN IMMIGRANT,” as if the hordes of Indians making their way to the U.S. are all budding entrepreneurs rather than computer janitors, convenience store clerks, or motel staff, as one would expect from a country with a mean IQ of 76, which is only slightly higher than the clinical threshold for mental retardation. However, even if Indians were the race of super-brainy Übermenschen that mass immigration proponents say they are, mass immigration is incompatible with scientific and technological progress on principle.

I touched on this in my article on Indian bodyshops, noting how mass immigration has led to the third worldization of the American labor market, with numerous Indians and other foreigners employed in redundant positions, in many cases doing little to no actual work. The conflict over labor and trade—two issues that are unavoidably connected—stems back to America’s founding, and it is because we chose to limit immigration and tariff foreign goods at key moments in history that America became a wealthy superpower. Throwing the gates open to foreign labor and goods is the direct cause of Americans’ increasing poverty, and unless they are closed, we risk regressing to a poor, irrelevant nation at the whims of foreign powers.

An American System for American Problems

The origin of what would later become known as the “American System” lies in Alexander Hamilton’s “Report on the Subject of Manufactures,” which he presented to Congress in 1791. The Founding Fathers largely agreed on the subject of immigration, which had been settled with the Naturalization Act of 1790, limiting American citizenship to “free white persons” who also possessed “good character.” Trade was a more contentious subject. In the “Report on Manufactures,” Hamilton argued for a policy of self-reliance and economic growth based on four key principles:

High tariffs to encourage industrial development in the U.S. and provide the federal government with revenue

High prices on federal land to generate additional revenue

Development of transportation infrastructure (termed “internal improvements”) to unify Americans and open up domestic markets for goods

A central bank to stabilize the U.S. dollar and regulate the activities of private banks

At the end of the American Revolution, Britain was by far the world’s dominant industrial power and remained the newly-independent America’s main trade partner. Hamilton argued that dependence on British industrial goods would prevent the development of domestic industry and effectively nullify the Revolution by making America economically reliant on Britain. By raising tariffs to make British imports uncompetitive, “infant industries” (a term used in 18th and 19th century political economy to describe America’s nascent industrial capacity) would be able to grow, making America wealthier and allowing it to maintain its independence:

The desire of securing a cheap and plentiful supply for the national workmen, and where the article is either peculiar to the country, or of peculiar quality there, the jealousy of enabling foreign workmen to rival those of the nation with its own materials, are the leading motives to this species of regulation. It ought not to be affirmed that it is in no instance proper, but is certainly one which ought to be adopted with great circumspection, and only in very plain cases. It is seen at once that its immediate operation is to abridge the demand and keep down the price of the produce of some other branch of industry—generally speaking, of agriculture—to the prejudice of those who carry it on, and though, if it be really essential to the prosperity of any very important national manufacture, it may happen that those who are injured in the first instance may be eventually indemnified by the superior steadiness of an extensive domestic market, depending on that prosperity; yet in a matter in which there is so much room for nice and difficult combinations, in which such opposite considerations combat each other, prudence seems to dictate that the expedient in question ought to be indulged with a sparing hand.

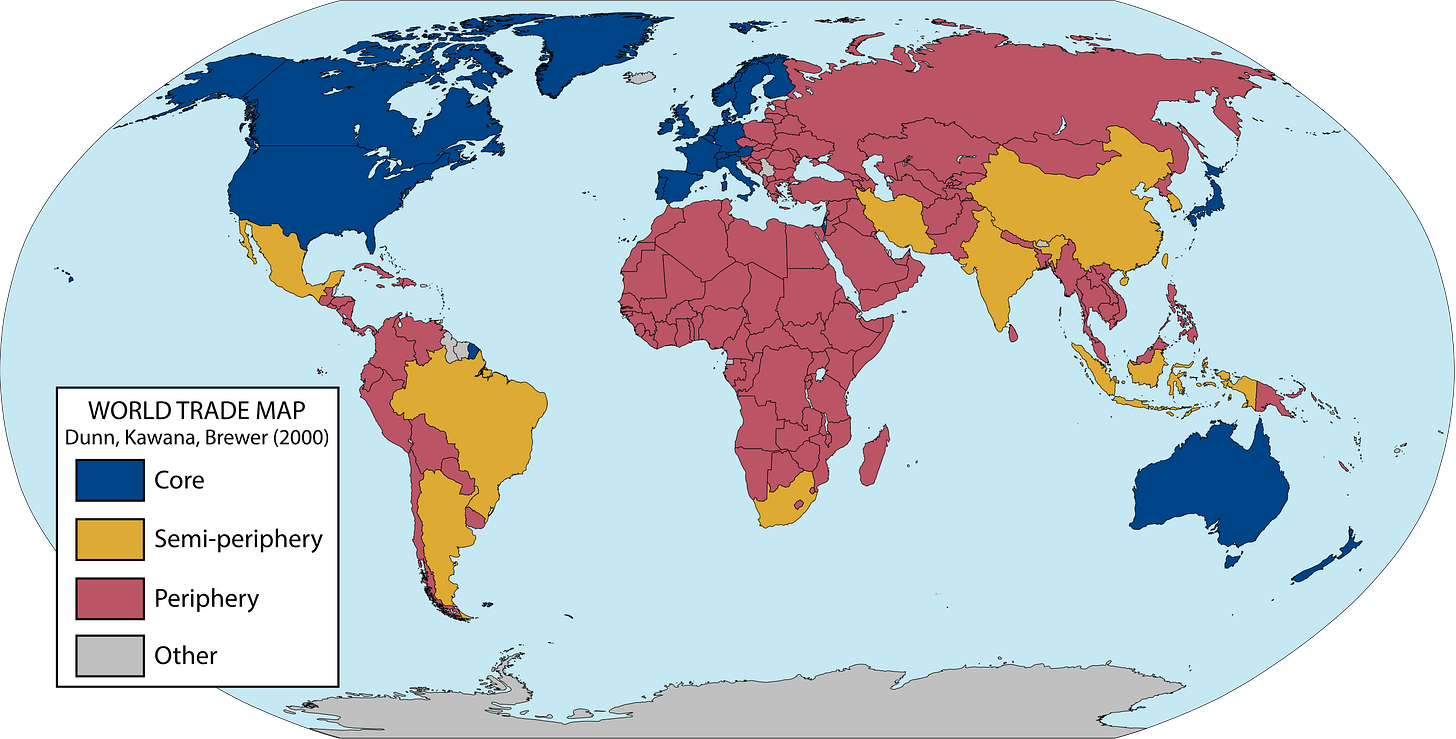

America did not begin life as a wealthy country, but was in fact relatively poor due to its underdevelopment relative to Britain, at the time the world’s undisputed superpower. Immanuel Wallerstein’s world-systems theory acknowledges this, classifying the U.S. as a “semi-periphery” country in the early 1800s due to its lack of industrial development compared to Britain, a “core” nation. Latin American nations such as Mexico are classified as semi-periphery or periphery to this day because they failed to embrace domestic development and remained dependent on wealthier nations for trade.

Similarly, Latin countries failed to invest in transportation infrastructure, precluding the development of domestic markets as well as fostering disunity between different regions. For example, Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula was more closely linked to New Orleans than Mexico City for most of the 19th century because it was easier to travel to the former than the latter, Mexico lacking both navigable rivers and a functional road/railroad network. The Texas Revolution of the 1830s was one of a series of secessionist revolts across Mexico as states on the fringes of Mexico—and thus isolated from Mexico City—proclaimed their independence in response to Santa Anna abrogating the Mexican Constitution and becoming a tyrant. Hamilton sought to use revenue from tariffs to finance “internal improvements” in the U.S.

Hamiltonian political economy applies to labor as well. Labor is ultimately a good, no different than what you buy in stores, and wages are the price of labor. Per the laws of supply and demand, an increase in the labor supply—such as that caused by mass immigration—causes a decrease in the cost of labor, aka lower wages, and vice versa. This was demonstrated during the “labor shortage” created by the COVID pandemic, as the shutoff of immigration and travel led many Americans to quit their jobs or demand better pay and treatment. Historians largely acknowledge that the Black Death, as terrible as its human cost was, ultimately led to the end of feudalism in Europe; the sheer amount of people it killed made labor scarcer and thus enabled serfs to bargain for more rights and higher wages.

A key plank of Hamilton’s platform is that restrictions on foreign trade and labor would encourage innovation (emphasis mine):

This is among the most useful and unexceptionable of the aids which can be given to manufacturers. The usual means of that encouragement are pecuniary rewards, and for a time exclusive privileges. The first must be employed according to the occasion and the utility of the invention or discovery. For the last, so far as respects “authors and inventors,” provision has been made by law. But it is desirable in regard to improvements and secrets of extraordinary value to be able to extend the same benefit to introducers as well as authors and inventors; a policy which has been practiced with advantage in other countries. Here, however, as in some other cases, there is cause to regret that the competency of the authority of the National Government to the good which might be done is not without a question. Many aids might be given to industry, many internal improvements of primary magnitude might be promoted, by an authority operating throughout the Union, which can not be effected as well, if at all, by an authority confined within the limits of a single State.

But if the legislature of the Union can not do all the good that might be wished, it is at least desirable that all may be done which is practicable. Means for promoting the introduction of foreign improvements, though less efficaciously than might be accomplished with more adequate authority, will form a part of the plan intended to be submitted in the close of this report.

It is customary with manufacturing nations to prohibit, under severe penalties, the exportation of implements and machines which they have either invented or improved. There are already objects for a similar regulation in the United States, and others may be expected to occur from time to time. The adoption of it seems to be dictated by the principle of reciprocity. Greater liberality in such respects might better comport with the general spirit of the country, but a selfish and exclusive policy in other quarters will not always permit the free indulgence of a spirit which would place us upon an unequal footing. As far as prohibitions tend to prevent foreign competitors from deriving the benefit of the improvements made at home, they tend to increase the advantages of those by whom they may have been introduced and operate as an encouragement to exertion.

This is easily observable in the modern world. Cheap-labor economies, such as Mexico, India, or the Philippines, contribute almost nothing in terms of scientific progress. There is no incentive to develop more efficient ways of doing things when labor is inexpensive, because people and corporations will always take the path of least resistance. The greater wealth of the North compared to the South in the 1800s is also evidence of this. The South’s reliance on a slavery-fueled plantation economy retarded its development, with the end result that by the time of the American Civil War, the South disastrously lagged behind the North in not only population but industrial capacity.

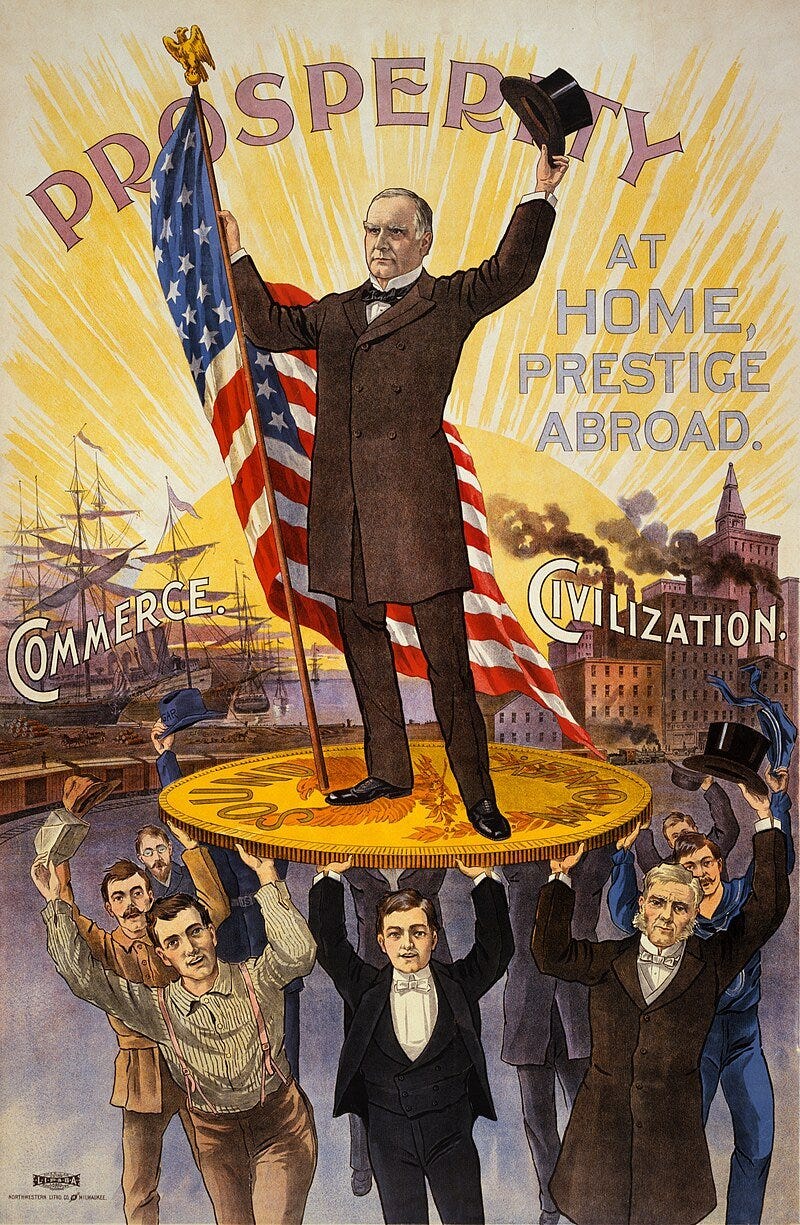

Hamilton’s ideas formed the basis of what would later become known as the American School, which was contrasted with the “British School” of free trade advocacy as promoted by figures like Adam Smith. Britain favored free trade because its greater industrial development and the resources provided by its empire gave it a decisive advantage in global trade. As late as the turn of the 20th century, protectionist politicians like President William McKinley ridiculed free trade as “British political economy.”

Slaves of a Defunct Argument

Most people are aware of how trade formed the basis of America’s original political divide, with Hamilton’s and John Adams’ supporters organizing as the Federalist Party and Thomas Jefferson’s supporters, who favored free trade and saw America’s future as being a republic of yeoman farmers, organizing as the “Democratic-Republican Party” (in quotes because this is actually a term invented by historians; the party was actually called the Republican Party, as distinguished from the modern Republicans). What libertarians and free trade advocates don’t tell you is that the argument was resolved by the 1810s in the Federalists’ favor.

The War of 1812 largely ended support for free trade and migration for a generation. America being cut off from international trade due to Britain’s naval blockade immiserated the country and nearly led to New England (at the time the primary center of American industry) seceding from the Union. This convinced Jeffersonians that tariffs and labor restrictions were necessary not only for economic prosperity but for national unity. Jefferson himself conceded that Adams and Hamilton were right in his private letters, stating that free trade advocates were “disloyal” and sought to “keep us in eternal vassalage to a foreign & unfriendly people”:

…he therefore who is now against domestic manufacture must be for reducing us either to dependance on that foreign nation, or to be clothed in skins, & to live like wild beasts in dens & caverns. I am not one of these. experience has taught me that manufactures are now as necessary to our independance [sic] as to our comfort: and if those who quote me as of a different opinion will keep pace with me in purchasing nothing foreign where an equivalent of domestic fabric can be obtained, without regard to difference of price, it will not be our fault if we do not soon have a supply at home equal to our demand, and wrest that weapon of distress from the hand which has wielded it.

While the Federalist Party faded away due to its association with New England secessionists, the Democratic-Republicans adopted Federalist trade policy under President James Madison, beginning with the Tariff of 1816. Consensus for Hamiltonian economic policy was all-but universal during the presidency of James Monroe, but began unraveling in the 1820s when the Democratic-Republicans split between supporters of Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams (the former of whom coined the term “American System”) and Andrew Jackson (who favored free trade). Clay’s and Adams’ supporters would reorganize as the National Republican Party and later the Whig Party, while Jackson’s supporters reorganized as the Democratic Party.

During the Jacksonian democracy era (1828 to 1860), the Democrats dominated national politics in part to their support in the South, which had disproportionate power due to the Three-Fifths Compromise. Southerners favored free trade because their banana republic economy was dependent on British trade and were unsympathetic to arguments that financing internal improvements would allow them to profit off trade with the North. The Democrats’ policy of low tariffs and mass immigration (it was during this time that large numbers of Irish immigrated to the U.S.) harmed American economic development, as did the failure to abolish slavery. Britain encouraged the Democrats, fearing that the American System would allow America to break the bonds of economic dependence on the U.K.

The Civil War was a war about trade policy as much as it was about slavery. Under Abraham Lincoln, the American System was finally implemented in full because the South had seceded and was no longer around to object. One of Lincoln’s chief economic advisors was Henry Carey, who authored The Harmony of Interests in 1851, rejecting “British” laissez faire capitalism and building on Hamilton’s economic ideas; Carey was also influenced by German-American economist Friedrich List, whose 1841 book The National System of Political Economy and its theory of “national economics” remains one of the central works of the American School. Britain and Canada clandestinely aided the Confederacy through smuggling and the sale of arms with the hope of weakening the U.S., and they were only prevented from overt intervention by public opposition in both countries to slavery. The Emancipation Proclamation was directed at Britain, France, and Canada as much as it was towards the Confederacy; by explicitly stating that ending slavery was the goal of the war, Lincoln sought to make foreign aid to the Confederacy morally untenable.

Lincoln’s policy set the stage for America’s rapid economic growth in the period following the Civil War, during which the U.S. went from an ignored backwater to one of the world’s dominant powers. Even Ayn Rand remarked in a speech (collected in her volume Philosophy: Who Needs It) that the late 19th century was one of the greatest leaps forward in terms of prosperity and scientific progress that humanity had ever experienced. While the Democrats were weakened by their association with the traitorous Confederates, the free trade and labor vs. protectionist argument continued, albeit with a decisive advantage for the protectionist side. A final showdown occurred in the 1896 presidential election, in which protectionist Republican William McKinley triumphed over free trade Democrat William Jennings Bryan, in part by marshaling support from both industrialists and urban workers.

Before becoming president, McKinley served in Congress and had established himself as America’s leading protectionist. In 1890, the McKinley Tariff was signed into law by President Benjamin Harrison, dramatically raising tariffs across a wide range of goods. Free trade economists falsely blame the McKinley Tariff for the Panic of 1893, even though the Panic happened under free trade Democrat Grover Cleveland, and in 1894, the Democrats replaced the McKinley Tariff with the Wilson-Gorman Tariff, which lowered tariffs by a whopping two percent and also imposed the first federal peacetime income tax. In his speeches, McKinley mocked free trade as “British” and “Confederate,” pointing out how the American System as established by Lincoln was the direct cause of America’s growing prosperity:

Protective tariffs are not only constitutional, but in our own experience they have proved wholesome to the great body of the American people. [Applause.] No nation in the world has done so well as ours; not one. Match it if you can under any circumstances the world over. [Applause.] We are the youngest nation on the face of the earth, and yet we have reached the first rank in mining, in manufacture, and in agriculture of all the nations the wide world over. [Applause.] But they said your protective tariffs, and especially the law of 1890, would build a Chinese wall around this country, and that you could neither get out or come in. [Laughter.] That is what they said in 1890. That is what they said in 1891. And if results did not overtake predictions, the Democratic party would be the greatest party of the world. [Laughter.] If that party could be only unembarrassed by facts! [Great applause.]

McKinley also pointed out that contrary to what free trade proponents claimed, his protective tariff actually brought down consumer prices while increasing real wages because they encouraged Americans to buy domestic products instead of foreign ones, stimulating the growth of new industries and creating new jobs. So much for “BUT AMERICANS PAY THE TARIFFS”:

‘Buy where you can pay the easiest.’ [Great applause.] And that spot of earth is where laboiwins its highest rewards. What has this Protective Tariff law of 1890 done? Why, it has increased factories all over the United States. It has built new ones, it has enlarged old ones. It has started the pearl button business in this country. [Laughter.] We used to buy our buttons made in Austria by the prison labor of Austria. We are buying our buttons to-day made by the free labor of America. [Applause.] We had 11 button factories before 1890; we have 85 now. We employed 500 men before 1890, at from $12 to $15 a week; we employ 8,000 men now, at from $18 to $35 a week. [Cheers.] The value of the output before 1890 was less than $500,000; it is $3,500,000 today. We are making some of the finest cotton and woolen goods that can be made anywhere in the world. You are making them in Massachusetts. They are being made all over New England. Why, we are making lace in Texas, the home of Mills. [Laughter.] We are making velvets and plushes in Philadelphia. When I was here, a little over a year ago, the complaint in every Democratic newspaper was that the tariff law of 1890 had put the tariff up on plushes, the garment that the poor girl and woman wore. Well, it is true that we did put the tariff up on plushes, but the price has come down. [Applause.] And we are making them in this country, giving employment to hundreds and thousands of workingmen…

After McKinley was elected president, one of his first acts was to replace the Wilson-Gorman Tariff with the Dingley Tariff, which raised tariff rates beyond those in the original McKinley Tariff. Not only did this not cause another economic panic, America went through a period of sustained economic growth, with the tariff remaining in place until 1909. The system established by Lincoln and McKinley largely stayed in place until the 1970s, with only minor adjustments, and immigration restriction was added to it with the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, passed by a Republican Congress and signed into law by Republican President Calvin Coolidge. It makes sense that a party founded on the principle of trade restriction would also move to restrict the flow of labor, another commodity whose cheapness was degrading the quality of life for Americans.

Britain would eventually be ruined by its obsession with free trade as America’s protectionist policies blasted the nation to the forefront of the world economy. In particular, British free trade led to the destruction of its automotive industry by Ford. Ford was able to import cars cheaply to the U.K. due to low tariffs, while British manufacturers could not compete in the much larger American market due to protective tariffs. China and India have been doing the same to the U.S. in recent decades, at least until Trump instituted new tariffs, taking advantage of free trade policy to dump their products cheaply in America while insulating their own economies from American competition.

The Canadian (and Australian) Dream

The American System was so successful that other newly independent British settler countries implemented their own versions of it. Canada’s National Policy, developed by its first prime minister, Conservative John A. Macdonald (in power from 1867 to 1873 and from 1878 to 1891), called for high tariffs to guard domestic industry as well as extensive government investment in infrastructure. In the 1911 election, fought largely on the basis of Liberal Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier’s pursuit of trade reciprocity with the U.S., the Conservatives successfully exploited fears that free trade would lead to the U.S. annexing Canada and defeated Laurier’s government at the polls. Decades later, the Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement (the forerunner to NAFTA) would spark a similar conflict, with Liberal leader John Turner famously arguing during the 1988 election that CUSFTA would reduce Canada to a “colony of the United States”:

Despite the majority of Canadians voting for either the Liberals or New Democratic Party (both of whom opposed CUSFTA), vote splitting lead to Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative government being reelected and CUSFTA was implemented.

Australia similarly took its cues from the American System. The “Australian settlement,” coined by journalist Paul Kelly, is used to describe the policy of domestic defense that the Australian government pursued following federation in 1901. They included high tariffs to protect industry, the “White Australia” policy of restricting non-white immigration, and interventionist policy on issues such as infrastructure and social welfare. The Australian settlement was largely dismantled from the 1960s to the 1990s, beginning with the abolition of the White Australia policy and ending with the deregulatory government of Labor prime ministers Bob Hawke and Paul Keating in the 80s and 90s. New Zealand pursued a similar deregulatory program during the 80s under Labour Prime Minister David Lange and Minister of Finance Roger Douglas.

Cheap Labor, Free Trade, and Stagnation

Many people have remarked at how the rate of invention and discovery has slowed since the 1980s. In contrast to the late 19th century and most of the 20th, when new inventions were frequently being developed that radically changed peoples’ lives, very little has occurred in recent decades on that level. The Internet was the last major invention that significantly altered and improved life for people, with maybe smartphones and AI—themselves relatively minor developments that stem from the Internet—being a distant second and third. No nation has sent men to the moon since 1972. We have shinier TVs and computers, but nothing has occurred since the early 90s on the level of the telephone, the automobile, the railroad, or other groundbreaking inventions.

This is a direct result of America and other Western nations opening the floodgates to cheap third-world products and labor. Hamilton was right; there is no motivation to innovate or improve when you can simply farm an infinite reserve of desperate Indians who will work 100+ hours a week for $5 an hour. Automation and the adoption of AI have turned out to be a false promise; corporations that blame AI for layoffs are simply replacing their American workers with Indians. Even Japan, which sought to use robots and automation to shore up its declining labor pool, is sipping from the poisoned chalice of mass Indian immigration.

No, the hordes of Indians coming to the U.S. are not budding Elon Musks who are ready to unleash their creativity on the world (something they mysteriously can’t do in their own country). They are field slaves whose sole purpose is to enrich themselves, their disreputable employers, and the Indian government. If you care about progress—genuine scientific and technological progress—killing the flow of cheap labor and goods from the third world should be your goal.

If you are an American, the only way to achieve the goals of ending mass immigration and free trade are through the Republican Party. The Democrats have always been the party of mass immigration and free trade, going back to “populist” hero Andrew Jackson and the Slave Power. It was a Democrat (Lyndon Johnson) who undid the immigration restrictions of 1924 via the Hart-Cellar Act, and it was a Democrat (Bill Clinton) who gave us NAFTA. Have you ever wondered why President Trump always invokes William McKinley in his speeches? He knows American history and MAGA is a return to the GOP’s original principles; the free-trade, open borders mainline Republicans and libertarians are entryists whose natural home is the Democratic Party. (Contrary to free traders claiming that tariffs are “socialist,” Karl Marx supported free trade because he saw protectionism as entrenching the power of capitalists, which dovetails with the Democrats’ recent pivot to open socialism.)

While Trump’s statements on H-1B visas are disappointing and must be resisted, immigration restrictionists have a far better chance of achieving change through the Republicans. Both Obama and Biden opened the floodgates and only Trump—or another Republican like JD Vance or Ron DeSantis—can close them.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider subscribing by clicking here. Most articles on this blog are free, but your support gives you access to paywalled articles and enables me to do this work. You can also make a one-time donation here (note: this does not give you access to paywalled articles, unfortunately). Follow me on X/Twitter, where I post stories more frequently, here.

Holy crap! Matt Forney shows how tariffs and reduced immigration fostered American prosperity in the past - and how it can be done again. Gotta read this one!!!

A great article and history lesson, sir. Well done.

...It's almost as if everything we've been told and taught about globalist economics being wonderful "cuz cheap consumer shit that falls apart in a few years" was not true! And look at how robust American manufacturing *was* - look at old appliances, ovens, engines, all of it. We made stuff built like tanks that lasted for generations.